Charmaine Ruddock, director of Bronx Health REACH, is a coalition of 50 community and faith-based organizations, funded by the Centers for Disease Control’s REACH 2010 Initiative to address racial and ethnic health disparities.

Happy Valentine (Not So Much) from President Obama

Happy Valentine (Not So Much) from President Obama

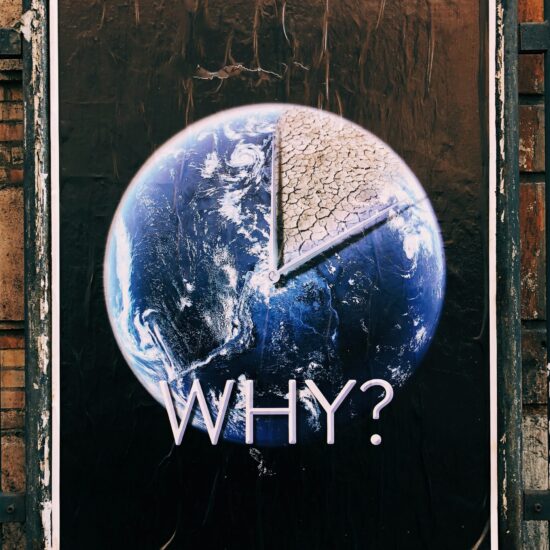

A week ago on Valentine’s Day REACH communities across the country received the kind of Valentine’s Day gift that had no love behind it. Included in the President’s proposed budget for FY12 was the defunding of the 12 year REACH program. REACH which stands for Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health is CDC’s cornerstone effort to address the stubborn and persistent gap between the health outcomes of whites and those of people of color be they Asian/Pacific Islanders, Blacks, Hispanics, Alaska Natives and American Indians. The genius of this effort is that in 1999 CDC took the unprecedented approach that the communities most affected by disparities should take the lead in addressing their disparities. By all accounts this was a major departure in public health. Heretofore, health disparities was something studied and researched with papers written and academic treatises produced but not much done in terms of addressing them in the local context where there were occurring and definitely not with a community based participatory approach. Enter REACH. In 1999, under the leadership of the then head of CDC, Dr.David Saatcher grants were made to 36 communities. Their mandate was to convene coalitions made up of people who work, worship, and live in the community –residents, healthcare providers, academic institutions, faith-based organizations, public health departments, elected officials, business people etc. The Coalitions first task was to put together a community action plan to address the prevailing disparity and its underlying contributing factors in their community. This was no knight in shining armor riding in on a white horse telling ‘those people’ what their communities should be doing. Instead, communities were given the resources to figure out what they needed to do and then go about doing it.

In 2003, the Government Accounting Office(GAO) at the behest of then Senate Majority Leader, Senator Bill Frist, MD wrote a report on racial and ethnic health disparity. In that report the GAO acknowledged the promising impact of the REACH initiatives. That promise of REACH communities since then has been realized in significant successes. Examples abound. In New York, the Bronx Health REACH Coalition working with others successfully eliminated whole milk from all New York City public schools cafeterias; launched a bodega initiative encouraging neighborhood stores to carry low-fat milk; working with 46 churches to implement health promotion programs, culturally appropriate for their faith-based setting; in 2010 worked with Bronx elected officials to introduce the Health Equality Bill in Albany to eliminate segregated specialty care in NYC academic medical institutions.

Bronx Health REACH is not singular in these accomplishments. Across the country other REACH communities made amazing strides in confronting many of the socio-economic-health system bogeymen strangling the health of their communities. As a result they are helping to transform their communities into healthier places for their residents. The south Los Angeles REACH group led by Community Health Councils, Inc. successfully advocated with the City Council forcing a moratorium on any further fast food establishments going up in a neighborhood over run by fast food. The Boston Public Health Commission REACH group recently mounted an innovative citywide advertising campaign utilizing television, web-based and outdoor advertising space to educate the entire city of Boston about disparities from one zip code to another. The Northern Manhattan Right Start REACH program closed the immunization disparity gap in Harlem and Washington Heights. For the Latino and Black children enrolled in their Start Right program they actually exceeded the national immunization rate for children 19-35 months www.cdc.gov/reach/pdf/NY_Columbia.pdf. The list of accomplishments goes on and on.

And yet, despite all of these, the justification given in the President’s budget was that departments of health in states and large municipalities are best positioned to accomplish the goal of eliminating health disparity. REACH grantees do not disclaim the important role that health departments can play in this effort. For many of us health departments especially the activist and progressive ones like NYCDOHMH are key partners in accomplishing the goal. But as Lark Galloway-Gilliam, President of the National REACH Coalition asserted in recent remarks, ‘In the failure to close the equity gap, time and time again [we see] in the tobacco, immunization, infant mortality and other state and national initiatives our communities are not funded directly at the outset and when it becomes clear the disparities persist, we are only then able to garner minimal resources.” The big lesson from the REACH initiative has been that CDC was right when they emphasized the critical role communities had in a national effort to eliminate racial and ethnic health disparities. In rebutting this new emphasis on ‘health systems of big cities and large metropolitan areas’, Neil Calman, MD President of the Institute for Family Health and the Principal Investigator for the Bronx Health REACH project put it well when he said, “They are looking for national solutions to a problem that can only be fixed with intensive and consistent work at a local level. Nobody knows that better than REACH grantees.”

Pingback: Tweets that mention Happy Valentine (Not So Much) from President Obama « CHMP -- Topsy.com / February 21, 2011

/