Joy Jacobson is CHMP’s poet-in-residence. Follow her on Twitter: @joyjaco

In the fall issue of Cerise Press, one of the best of the many online literary journals to debut in recent years, I review Asti Hustvedt’s Medical Muses: Hysteria in Nineteenth-Century Paris, the story of three French women—Blanche Wittmann, Augustine Gleizes, and Geneviève Basile Legrand—whom Jean-Martin Charcot treated for hysteria at the Salpêtrière Hospital in the 1870s. A hysteric’s symptoms ran the gamut from hallucinations to stigmata, and treatment often involved hypnosis, a torment that granted only brief reprieves.

What makes Hustvedt’s book so absorbing is not only her in-depth narration but also the relevance these women’s lives and illnesses have to us today. From my review:

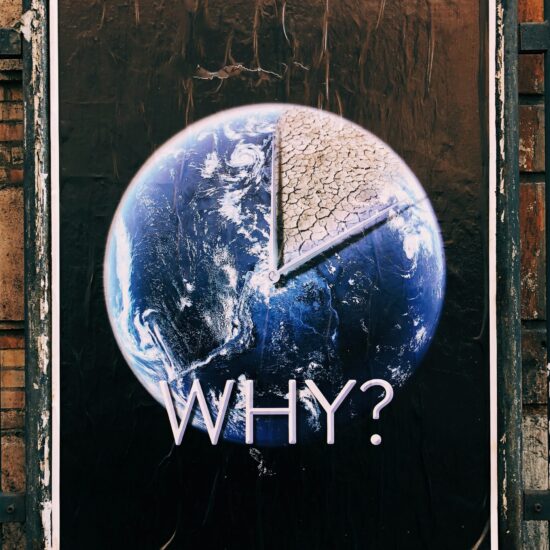

Hustvedt writes that our current-day “epidemic” is not hysteria but depression, which Western medicine neither diagnoses nor treats with certainty, as is the case with so many other syndromes: anorexia and bulimia nervosa, autoimmune diseases, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome. Hustvedt notes that women receive such diagnoses in far greater numbers than men, and despite some advances in diagnosis and treatment, the medical model still regards many of them as mysteries.

Jessa Crispin, who writes the Bookslut column for The Smart Set, also reviews Hustvedt’s book, along with Sybil Exposed: The Extraordinary Story Behind the Famous Multiple Personality Case, by Debbie Nathan. Crispin dissects the 1980s psychiatric culture that produced “hundreds of thousands” of diagnoses of multiple personality disorder and makes explicit parallels between that time and 1870s Paris:

We learn how to be mad, the same way we learn how to be male or female, or how we learn how to participate in society. We look to others we respect and imitate their behaviors. We follow the instructions of teachers and parents, and we are subtly punished or rewarded for various quirks until we learn to mold ourselves in a certain way to avoid responses we don’t like and attain the responses we do.

And in the summer issue of the American Scholar, Laurie Murat writes that in Medical Muses, Hustvedt “deplores our modern tendency to despise diseases rooted in psychic frailty.” It’s that frailty, and the social circumstances that created it, that Hustvedt so brilliantly documents.

djmasonrn / November 6, 2011

Fascinating analysis. I recall from an undergraduate psychiatric nursing course that included community-based clinical experiences (the West Virginia University School of Nursing was way ahead of its time in the late 1960s), my professor remarking that mental illness is treated differently in small communities. I still have this mental image of a person with some psychosis being looked after by friends and neighbors in the community. Shelter and food were provided as needed. People interacted with the person instead of crossing the street in avoidance. The person was just different and needed help from the community–and the community provided it.

There is also an analysis of women’s hysteria in the1900s that framed it as arising from a physiological, sexual congestion. You can still find photos of the physician stimulating the female patient (with a vibrator once electricity was on the scene) to obtain “release”. The connection that was made between women’s sexuality and hysteria suggested to some a fear of women’s power and anger. Heaven forbid the “crazy woman”.

/