This post is by CHMP’s graduate fellow, Amanda Anderson, RN. Amanda is a practicing bedside nurse in Manhattan, and a student in the Hunter-Bellevue School of Nursing‘s dual MSN/MPA program with Baruch College. At HBSON, she co-directs The Nurses Writing Project, a nurse-specific writing program that uses peer-based collaborative writing assistance and reflective writing practices to grow nurse leadership via the written word. She blogs here, and for a number of other nursing sites. Find her clips via her blog, This Nurse Wonders. She tweets @12hourRN.

She was gone, and we knew it. Her heart was just too sick and just too tired to benefit from the chest compressions we had started moments ago. We knew the code would bring only trauma to her failing body, but she was so young, and we had already done so much, and this is what she wanted. Besides, we loved her.

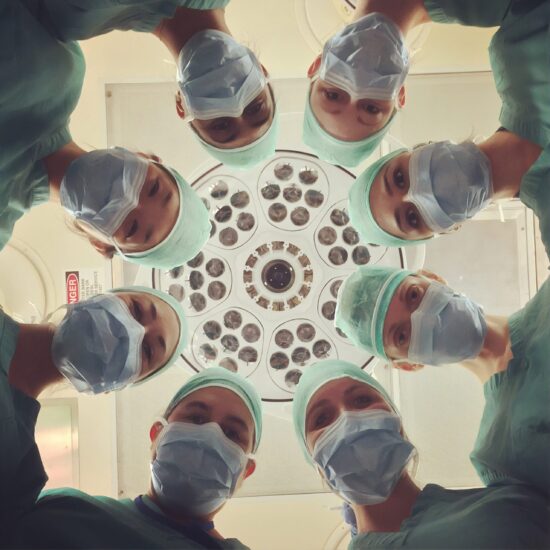

With code bell blaring, our attending for the night – young, too, but healthy – ran to the head of the bed to intubate. Shaking hands barely wrapped in the first gloves she could find, she pried open her blood-filled mouth. We tried to clear this blood that poured – blood full of disease and fear, blood accidentally infected at birth.

Thumping, splashing, yelling – the violence of the code sent red waves of grief over us as we worked. Somehow, someone tied masks on our faces long after our grim care began – we spent no moments thinking of risk, speeding forward for the life we so desperately wanted to save.

In health care, whether we love our patients or not, we daily risk our health on their behalf. We risk needle sticks, violence, and the impervious chance of infectious spread. Ebola brought this risk into the view of American media, but its spotlight simply illuminates the daily chances we take to care under the shadow of HIV, Hepatitis or even pneumonia. The American Nurses Association, and state boards of nursing, clearly state that our ethical duty as nurses comes irrespective to patient diagnosis. Besides, I don’t know a single provider that would sit back or deny care to a patient in life-saving need.

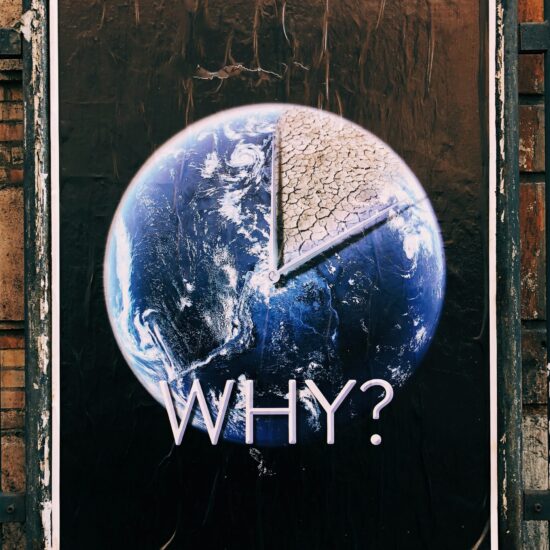

But in a strange little article, tucked deep within the New York Times Tuesday Science section this week, Lawrence K. Altman writes of a New York City bioethicist’s industry-wide call to withhold cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and resuscitative care, to those diagnosed with Ebola. The week’s Ebola news lessened since the prior’s media frenzy, but this piece – viewed against the backdrop of the Dallas transmissions, a persistently raging epidemic in Africa, and CDC squabbles – snuck in as a puzzling commentary, one that should not sit void of nursing voice.

Altman discusses the statement bioethicist, Dr. Joseph J. Fins, of New York Presbyterian Hospital Weill-Cornell, made on the Hastings Center’s website last week. According to Fins, Ebola poses far too much risk for health care providers performing CPR, and because of the extensive PPE application required, patients requiring CPR may suffer extensive brain damage by the time providers are prepared to initiate it. Considering this, Fins states, “Unilateral do-not-resuscitate orders would seem justifiable under these circumstances, if surrogates do not otherwise agree to a DNR order.” While the article and bioethicist argument expose a gap in current medical conversation about Ebola treatment in light of resuscitation, neither makes efforts to consider the personal experience of providers – particularly nurses – instructed to withhold potentially life-saving care.

A nurse’s voice is vital here. As we saw through the infected nurses in Dallas, and through the subsequent media debate about Ebola care and PPE needs, nurses are in the forefront of care – and should likewise be in the forefront of policy creation. In my opinion, there are two important missed opportunities for nurse voice in this article – a discussion of the very frequent nature of risky, and often futile CPR care given to patients infected with common diseases such as HIV and Hepatitis, and a personal telling of the potential moral distress from withholding care on a deserving patient, regardless of risk to providers.

While Fins’ arguments prove logically valid, and in his Hasting’s Center statement, he makes them with great deliberation, Altman’s article for The Times speaks very little about the fact that we often provide aggressive, full-court press care to high-risk, medically futile patients every day. These patients – like the Ebola patients Fins’ suggests would benefit little with CPR – often have little or no prognosis for recovering from CPR, an intervention that is sometimes misunderstood by patients. National facts mirror our overtreatment and misinterpretation of CPR at end of life – even though 80% of people with chronic illness say they’d rather avoid the hospital when dying, half of Americans breathe their last breaths as inpatients, undergoing care that is often not intended for cure. Whether this daily care is futile or not, to broadly limit resuscitation based on a single diagnosis – Ebola – should not come without an interdisciplinary discussion of the realities of current practice, and the possibility for great ethical dilemma when singling out a diagnosis.

A nurse’s voice in this article might call attention to our history of embracing risk to care for populations with grave illness, but could also highlight the personal side of resuscitation care. To watch a patient die while believing that your care might prevent, or at least attempt to prevent death, is a narrative that cannot be left out from this discussion. A nurse might speak about health care providers’ inability to turn off our ingrained call to beneficence simply based on diagnosis. And a nurse bioethicist should call attention to the extensive research that surrounds the subject of moral distress – knowing the right thing to do, and being kept from doing it – and the benefits of moral courage, especially in situations of high risk.

Barring providers from performing CPR may protect from the danger of Ebola infection, but it could expose us to the trauma of withholding care. As active participants in CPR care, a nurse voice is needed here – to solve the dilemma of Ebola care, but also to champion the critical conversation about our daily interactions with risk and futility.

She died shortly after we found her breathing tube and filled it with our own plastic substitute. Blood on her face, on her neck, on the bed. Dark blood, like molasses spilled. Her mother told us to quit the physical work of the code, her sister told us to leave the tube in her mouth, and her father told us they’d wait for her heart to slow and stop itself. We had paused the inevitable, we had worked, we had fought – all of us leaving, stained from the inside, out. Passing a bottle of hydrogen peroxide between us, our minds stayed close to the heart of her life, far from our cleansing ritual.